Podcast: Play in new window | Download

In this episode Gregg returns to the notion of interpretation and its importance, particularly for Christians, given to the extent a central text—the Bible—informs and grounds their beliefs.

Gregg explains that interpretation is a way of engaging with the world that we are always already doing. This is so much the case that interpreting is not so much an action that we perform but something that is inherent to our way of being in the world.

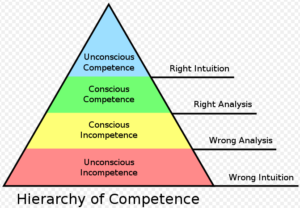

In this way, we can think of our interpretation according to the four levels—or stages—of competence, ranging from unconscious incompetence (where we are unaware of our inability) to unconscious competence (where we are so skilled that can perform an action without paying attention to it).

In most cases, adults interpret the world around them with unconscious competence, such a seasoned driver responding to a Stop sign.

Gregg notes that interpretation, like real estate, is dominated by three laws. So, similarly to “location, location, location” the three laws of interpretation are “context, context, context.” Further, it is important to know the value and implication of the various components within a text. For example, differentiating between the role played by words and the role played by sentences. In short, words indicate, sentences mean. Thus the context (and therefore meaning) of words is set by their context within a sentence, and the sentences sense is informed by its context within the larger writing, and so on.

Gregg also highlights the importance—and distinction between—truth claims and truth values. Gregg notes that often he sees these two confused by Christians, which gives rise to interpretive problems. This typically happen in one of two ways. On one hand, Christians at times hold assumptions that are unfounded, such as theologian Rudolph Bultmann presupposing that the miraculous is impossible. Such a view amounts to ruling “out of bounds” any unique action in the historical past, which seems unfounded (and certainly unprovable). On the other hand, Gregg’s experience is that Christians often “conflate” truth claims and truth values by supposing or implying that a truth claim can act as its own validation.

Understanding this latter point is particularly important where Christians are in dialogue with non-Christians, because no claim in itself represents or contains the validation needed for outsiders to a given perspective to believe that view or perspective. So instead of imagining that truth claims represent (or contain) their own validation, Gregg advises that wherever possible Christians offer personal validation for their claims (i.e., answering the question “What makes this claim believable to you / On what basis do you believe this claim?”)

Gregg highlights the disjunction between truth claims and truth values by examining the two main ways that he has experienced Christian ‘testimonies’.

In the first instance, many ‘testimonies’ claim too much out of too little. These sorts of accounts appear as rather vague or loosely connected events that involve some form of divine intervention, presence or relevance. These accounts often have little direct or obvious links to God, but because ‘testimonies’ are supposed to “move people” toward belief in God so this puts the teller into a position where s/he often ends the account with a dramatic—but not coherent—punchline that amounts to: “God did this!” or “God was here!”

Instead, Gregg suggests that Christians need to consider what it is about an experience or situation that renders particular Christian views believable, and focus on communicating this.

Second, where Christian testimonies do have substance they often are communicated as legal testimony—as conveying information such as dates, circumstances, and outcomes. Instead again, Gregg charges that the focus of Christian testimony about God is not the events primarily but the interpretation that one gives them, and primarily the notion that the interpretation that is given is the best and none other will do.

This involves tremendous thought and reflection, and also being open to putting one’s experiences and interpretations thereof “in the dock:” to tell others our stories of how we have experienced God and allow others to give us feedback on the clarity, viability and even believability of the experiences and / or how we have interpreted them.

In Gregg’s view, focusing Christian testimony on how we have interpreted those experiences that have been key to leading us to believe in (and commit to) Christianity allows listeners the chance to understand how the teller has linked these events with God to be compelled by the links, making Christian belief both sensible and convincing.

Gregg notes that just as interpretation is crucial to understanding properly the divine story, so to it is crucial to understanding one’s own story and historiography. And both God’s story and one’s own story are essential both for living well in the world and as connecting best with God. This is of great importance yet greatly misunderstood within Christian culture, such that many Christians believe that their own story is supposed to be put aside they are instead to focus entirely on God’s Story. Gregg relates this to Christians lacking conceptual savvy and having a rather sparse conceptual toolbox (where we lack such concepts as being “narrators” in our own lives, concepts that allow Christians to view the importance of their own story in a way that can be complimentary—and not simply conflictual—with the divine story).

Gregg ends by re-emphasizing the importance of feedback and seeking knowledgeable, competent sources of feedback. Christians need the Bible and need more than the Bible, and becoming competent with a variety of feedback sources and types will allow Christians to be better able to integrate their faith and the lives / living in the world.